Throughout art history, women have struggled to break the shackles of the muse and gain the same footing as male artists. The battle for equality in the art world goes beyond recognition or exhibitions and asserts itself in auction houses. Yet, on October 5, Jenny Saville’s Propped (1992) sold for an astounding £9.5 million at Sotheby’s London, breaking the record for the most expensive painting by a living artist. The large-scale self-portrait portrays the nude artist seated and staring down at the viewer. Saville paints her flesh using strokes of subtle blues, yellows, and pinks to highlight her “imperfections” and, more importantly, to challenge preconceptions of beauty. The monetary difference between Saville’s record-breaking sale and that of her male counterpart, Jeff Koons, is £35.9 million. Although the selling price of Propped is a victory for working women artists, the lack of female artwork in auction houses and the subsequent price discounts of the few female artworks that do go to auction, highlights the inherent bias in the art market and in our collective culture against women and their work.

Born in 1970, Jenny Saville studied art at the Glasgow School of Art from 1988 to 1992 and is a member of the Young British Artists (a loose group of artists who began exhibiting together in 1988). The artist is represented by Gagosian, a global art gallery established in 1980. Throughout her oeuvre, Saville explores the fragility, rejuvenation, and decay of flesh informed by the extension of her study beyond the classroom and into the operating theaters of surgeons and morticians. Saville creates her large-scale artwork with thick layers of oil paint that are then applied to canvases using expressionistic smears, strokes, and scrapes. Her impasto style renders her nudes and portraits as almost grotesque, which is underscored by dramatic lighting that illuminates every crevice and flaw of the human body. Her self-portrait, Propped, was brought to the international art stage at the 1997 exhibition, “Sensation: Young British Artists,” at the Saatchi Gallery of the Royal Academy in London. This same exhibition featured several works of artist Damien Hirst, whose Lullaby Spring sold for over £9.6 million in 2007. SHIFT, another of Saville’s artworks comparable to Propped in terms of size and year of sale, sold at Sotheby’s London in 2016 for £6.8 million.

Using an exclusive data set inclusive of over 2.6 million sales completed at Western fine art auctions from 2000 to 2017, Fabian Y.R.P. Bocart, Marina Gertsberg, and Rachel A. J. Pownall found clear evidence of a glass ceiling for female artists. Their report, “Glass Ceilings in the Art Market,” further revealed that female artists have fewer chances to evolve from the primary market (gallery) into the secondary (auction), where works by male artists account for 96.1% of auction sales. A different study, “Is Gender in the Eye of the Beholder? Identifying Cultural Attitudes with Art Auction Prices,” analyzed 1.5 million auction transactions in 45 countries and found that paintings by female artists are sold at an average discount of 47.6%; in countries with greater gender inequality, the price disparity becomes more pronounced.

This underrepresentation of female artists in the art market can also be seen in art museums: approximately 50% of western contemporary artists are women, but several sources cite that women make on average 20% less than men and are also less likely to have solo-exhibitions at museums. Statistics from collectives such as the Guerilla Girls show that women have been relegated to the inspiration instead of the inspired. Women were meant to be beautiful and charismatic. Jenny Saville’s work confronts ideas of what the female nude should be is and instead creates powerful paintings that embrace the blemishes, the folds, and the cellulite. The artist’s record-breaking accomplishment cannot be understated, but it should underline the inherent prejudice against women in art history. One can only hope that with other female-led movements, such as “Time’s Up,” Saville’s triumph is only the first step in a new direction for contemporary art.

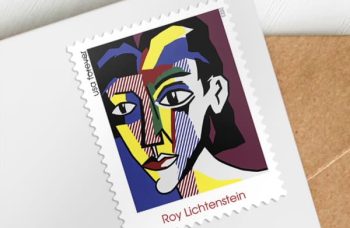

Image: Jenny Saville, Propped, 1992. Oil on canvas. 84 x 72 inches / 213.4 x 182.9cm © Jenny Saville. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian.