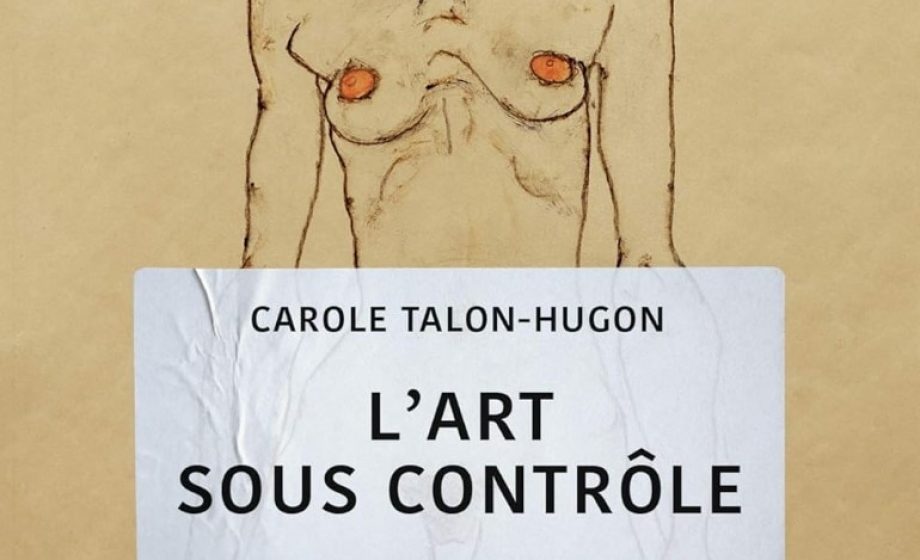

The most recent book by Carole Talon-Hugon has just been published by éditions PUF. Entitled L’art sous contrôle (Art Under Control), the book provides an overview of contemporary art where the content and political and social agenda is increasingly apparent whether through the works themselves, the discourse they produce or the establishments that display them. This essay also examines the recent rise of censorship.

Carole Talon-Hugon’s thesis focuses on establishing a relationship between these two phenomena. In the author’s view, when contemporary art’s purpose is no longer esthetical but ethical, it leads to a new relationship with works considered moral thereby allowing the emergence of condemnation and requests for censorship.

Carole Talon-Hugon characteristically questions art’s current status compared to previous eras. Building a four-part argument, she defines the specificities of morality currently operating in art today. If in the past some artists had social aspirations, it had to do with transgressing prevailing morals in order to reclaim their freedom of expression and not to defend the values of the society of their time. Similarly, while throughout history there have always been viewers who condemn art and seek to prevent its display, censorship has not always been exercised in the same way; it focused on the content of the work and not the personality of its author.

Consistent with the concerns that made her previous books successful, the philosopher demonstrates how this ethical paradigm reconfigures the concept of artist, work, esthetic value and art criticism and asserts that the appearance of criteria external to the field of art continues the movement of dis– artification begun by the radical 20th century avant-garde. Her essay also underscores how this has transformed notions about ethics. Far from concerning humanity altogether, the notion of ethics, as understood in the context of art today, is diverse. It is linked to societal claims of individuals joined by criteria such as gender, race, sex or social status. This new ethic, highlights the differences to the detriment of the similarities thus creating fragmentation in which the discourse of the other is no longer audible, which consequently prompts requests for censorship rather than discussion.

Carole Talon-Hughes does not limit herself to a single observation, she questions what now seems to be obvious; that art must have social aspirations and that it should be judged according to moral principles. In her usual clear style, she also reminds us that the artist’s societal grievances as well as the viewer’s requests for moral censorship are based on a presupposition that has not yet been verified; the real effectiveness of art in social and moral matters. While the author goes into detail on the theories of many other philosophers throughout history who have approached this question, she places particular emphasis on our era where art’s visibility cannot compete with other modes of expression that proliferate through screens. She reminds also that the audience sought by contemporary art is often the one likely to support a cause; that they are anti-globalists, feminists, anti-colonialists or ecologists. It is time, according to Carole Talon-Hugon, to reconnect with an independent art and a universal ethic.