Dutch modernist Piet Mondrian, known for his striking colour block paintings, has made headlines twice recently. Once for a repatriation lawsuit involving a German museum and a second time for extensive conservation research getting started in Switzerland. Art Critique takes a look at both.

Restitution

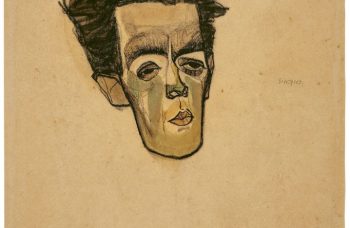

The children of American abstract artist Harry Holtzman have filed a lawsuit in a US District Court against the Kunstmuseen Krefeld in Germany. The suit claims that Holtzman’s children, who are also the heirs of the late Dutch artist Piet Mondrian, are the rightful owners of four paintings by Mondrian and that the museum has declined to return them.

Before his death in 1987, Holtzman helped Mondrian escape Europe in 1940, fleeing from Nazi rule, and settle in New York City. Holtzman would eventually become an expert, himself, in Mondrian’s works, the executor of Mondrian’s estate, and the sole heir to the Dutch artist. Holtzman’s children are now fighting for the return of four paintings and damages for an additional four that were allegedly loaned to the Kaiser Wilhelm Museum, operated by the Kunstmuseen Krefeld, and never returned.

The suit claims that in 1929, Mondrian loaned eight paintings to the Kaiser Wilhelm Museum for an exhibition that never came to fruition. By October of 1933, the Nazi regime took over the museum, installing Burkhard Freiherr von Lepel, now a known art looter for the Nazis, as director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Museum. Mondrian’s paintings were still held at the museum but when the Nazi’s began to label modern art and artists “degenerate,” the suit claims that the only reason the works “escaped Nazi hands” was because they were not included on the museum’s inventory.

It wasn’t until 2011 that Holtzman’s heirs claim they learned of their potential rights to the paintings when they were reached by Monika Tatzkow and Gunnar Schnabel, researchers looking into art dealer Sophie Küppers, who worked with Mondrian, and artworks lost during the Nazi era. According to Tatzkow and Schnabel, it appeared that the Kaiser Wilhelm Museum had never officially or lawfully acquired the eight Mondrian paintings.

In 2017, the heirs contacted the Kaiser Wilhelm Museum prompting an investigation but in 2018, the museum declined to return the artworks and the city of Krefeld rejected the claims. That same year, the Holtzman heirs made their claim to the Mondrian paintings public although the museum upheld their right to the paintings telling the New York Times, at the time, that Mondrian “regularly gave away paintings for which he no longer had any use.”

Four of the paintings included in the lawsuit still reside in the Kaiser Wilhelm Museum’s collection although another four, for which the heirs are seeking damages, were sold in the 1950s. In all, the works are valued at around $200 million and the 1950s transactions are deemed “wrongful” by the suit alleging they are “in violation of the British military law that governed Krefeld at the time.”

Conservation

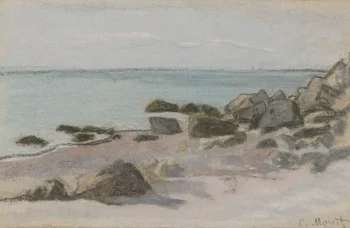

Ahead of a 2022 survey of more than 80 artworks by Mondrian to be held at Basel’s Fondation Beyeler, the museum is performing extensive conservation research on their own seven works by the artist. Led by curator Ulf Kuster, researchers are delving into a thesis of their own suggesting that Mondrian never abandoned nature in creating the abstract works we know today.

“The interesting thing with Mondrian is the dating of his work, and there is some research to be done on this, and some of it has been done, suggesting that his development from figuration to abstraction is not so straightforward,” said Kuster according to Artnet News. With their research, the Fondation Beyeler hopes to inform audiences about the lack of distinction between figurative work and abstract work that exists for some artists. “If you talk to Peter Doig or Neo Rauch, they don’t see this very scholarly distinction between figuration and abstraction,” continued Kuster. “The more you get involved with Mondrian, the more you see this difference didn’t exist so much. He always said he was coming from nature.”

In addition to their research into the “why” of Mondrian’s work, the museum will be performing extensive studies on their Mondrian paintings to better understand the “how” as well. From a cursory glance, Mondrian’s artworks seem straightforward and precise. However, at their surface, the works are exceedingly complex. Particular attention will be given to the way that Mondrian laid in the black lines separating his colour blocks, which tend to be slightly raised compared to the black.

“There are letters and quotes and drawings, so there is some information about how he made his works,” says Markus Gross, head of conservation for the Fondation Beyeler. “But there is no literature on his working process. So we want to do a mock-up reconstruction of a painting to better understand his techniques.”