Former art forger John Myatt—who in the 1980s forged hundreds of “masterworks” and fenced them to institutions as venerable as London’s Tate Gallery—recently told reporters that in his opinion, pulling off such a scheme is “just as easy today”. Recent events would seem to prove Myatt’s point. In late 2019, Prince Charles’s charitable foundation was caught up in a massive art scandal in which disgraced playboy James Stunt apparently commissioned copies of famous artworks from noted forger Tony Tetro and then tried to pass them off as genuine articles. Auction house Sotheby’s has been embroiled in legal battles after the auction house sold a forged “Dutch old master” for $10.75 million—and the fallout continues to spread from an ill-fated exhibition at Ghent’s Museum of Fine Arts.

The exhibit, on Russian avant-garde art, was forced to close early after some of the field’s greatest experts claimed that many of its artworks were fake. The museum’s reputation has been dealt a serious blow, while its director has been suspended from her post for nearly two years. Last month, Belgian police arrested the pair of collectors at the heart of the drama—Igor and Olga Toporovsky, who stand accused of forgery, fraud and money laundering.

The Toporovskys have yet to be officially charged with any crimes, but certain elements of the tale—a married couple, professing to have picked up an astonishing collection thanks to a turbulent time (in the Toporovskys’ case, the chaotic days after the fall of the Soviet Union)—will remind any art insider of the surreal saga of Wolfgang Beltracchi. Beltracchi, dubbed the “greatest art forger of our time”, once seemed set for a long stint behind bars after it came out that as many as 300 of his forgeries hung in the world’s major museums. Eight years later, Beltracchi has managed to parlay his notoriety into a lucrative post-prison career, while the art world still grapples with the questions his massive fraud provoked.

What, exactly, is the line between imitation and criminal forgery? For much of history, well into the Renaissance, artworks were appreciated more for their aesthetic value than for the artist’s true identity. This changed as art gradually became considered a commodity—unauthorised reproduction of a work became considered forgery and fraud.

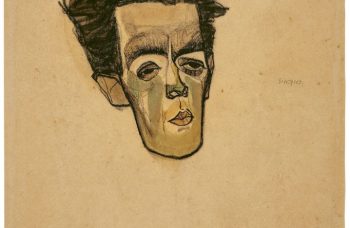

One might say, then, that Wolfgang Beltracchi—perhaps one of the most polarizing figures in the entire history of art—came along just a little too late for his talents to be appreciated. At the heart of the controversy surrounding Beltracchi, of course, is the question of where exactly these talents lie: is he a genius artist in his own right, a brilliant forger who took the work of well-known painters to another level? Or is he a run-of-the-mill copyist who ascended to glory thanks to his outstanding self-presentation skills? And how did Beltracchi manage to sucker some of the world’s most renowned art experts into validating his works as newly-discovered masterworks by the likes of Max Ernst or Fernand Léger?

The Hippie Prodigy

It’s clear where Wolfgang Beltracchi’s— born Wolfgang Fischer in Höxter, Germany—interest in art first came from. His father was a house painter and muralist who produced cheap copies of Rembrandts, Picassos and Cézannes on the side. It was quickly obvious that Wolfgang’s talents far exceeded his father’s, however. At the tender age of 14, he shocked his family by painting a decent “Picasso” in just a day.

While Beltracchi was clearly an art prodigy, he was less gifted in the classroom. Never studious, he dropped out of school at age 17. He eventually enrolled in an art academy in Aachen, but bored by courses far beneath his artistic abilities—in an ironic twist, one instructor even insisted that he must not have actually done his assignments, because the work he was handing in was “too good” to be his—he skipped most of his classes, bought a Harley-Davidson and joined the burgeoning hippie movement.

In later years, Beltracchi has recalled spending much of his time getting high with U.S. soldiers stopping over at the nearby NATO base on their way home from Vietnam tours, and has tried to use the chaos of the time to explain his criminal bent. “You don’t wake up one day and decide: ‘I will become an art forger’”, Beltracchi told German arts magazine The Forest. “I was born in 1951 and my parents belonged to a generation that had been betrayed twice by the political elite […] my mother became an inactive anarchist and I grew to be a ‘freak’ who didn’t care about the established society in the Sixties.”

Beltracchi’s nomadic and laid-back way of life continued well past the turbulent Sixties. As he wandered between a Moroccan beach and the streets of Barcelona, London and Paris throughout the 1970s and into the early 80s, his artistic talent manifested itself more prominently, and he began to make a decent living by selling and buying paintings at antique markets.

The journey to the dark side

Unlike someone like Tony Tetro, who never had much interest in painting under his own name and moved swiftly into forging masterworks, Beltracchi made token attempts to paint original creations. He even had some early success, contributing three works to a prestigious art exhibition in Munich in 1978. Even then, however, Beltracchi was drawn towards “an outlaw life.” As a carpenter who worked on one of the forger’s opulent homes put it, “He struck me as a person who had always lived…on the borderline”.

Beltracchi finally crossed that line when he got a bargain on a pair of winter landscapes by an unknown 18th century Dutch painter. The future forger had noticed that Dutch paintings which depicted ice skaters sold five times the price of those without them. Unhesitatingly, he painted the skaters into the scenes and resold them at a considerable profit. Soon, he was buying old wooden frames and painting skaters from scratch, selling them as authentic works by old masters.

Beltracchi tried going straight in 1981, founding art gallery Kürten & Fischer Fine Arts alongside a Düsseldorf real-estate salesman. Being on the up-and-up didn’t sit well with the German forger, however; not only was Wolfgang deeply unhappy sitting in the office all day long, his business partner soon accused him of stealing paintings—allegations which Beltracchi vehemently denies to this day.

Out of work and money, he turned to his small-time forgery racket – and scaled it. He abandoned old masters to focus on early-20th-century French and German artists—a strategic choice, since the pigments and frames from that period were much more accessible. The volume of his work depended on his inspiration as well as his need for cash. “Sometimes I’d paint 10 works in a month, and then go for six months without doing any,” he explained in a 2012 interview to Vanity Fair. He revisited some of the same artists over and over again— German Expressionist Johannes Molzahn became one of his particular specialties. In an early sign of how convincing his forgeries were, he sold a dozen of phony Molzahns—including one to the artist’s own widow—which fetched up to $45,000.

The accomplice

Wolfgang, however, didn’t move into the big time until he met Helene Beltracchi, an occasional antique dealer who worked for a movie production company, in 1992. The art market was in a slump at the time, and Wolfgang had temporarily put his forgery business on hold to travel the world filming a self-written documentary about pirates. When Helene met Wolfgang for the first time, he struck her as “a lunatic”—one article about the Beltracchis’ crimes would later pointedly note that “the line between genius and madman is thin”—but she soon came around, admiring his intelligence and his perfectionism.

As for Wolfgang, he was instantly enamoured with the 34-year-old Helene. “The first time I saw Helene, I said to myself, I’m going to marry this woman and have children with her,” Wolfgang said in an interview. The forger par excellence was right—Helene quickly left her longtime boyfriend and moved in with Wolfgang. They never finished the pirate documentary—according to Vanity Fair, they left the cast and crew stranded in Majorca—choosing to focus on a different kind of piracy: fleecing art collectors.

Wolfgang’s inkling that he had met his perfect match in Helene—he once referred to themselves as “the Bonnie and Clyde of the art world […] only with pencils”—proved right. Helene found out the truth about Wolfgang’s secret business “on the first or second day” of their relationship, but was relatively unfazed and soon agreed to be her husband’s accomplice.

Wolfgang and Helene’s first foray into the dark side of the art world went easier than they might have expected. After they informed Lempertz—a high-end auction house in Cologne—that they had a painting by early-20th-century cubist Georges Valmier for sale, a representative from the auction house swiftly picked up the “Valmier” for 20,000 Deutsche Marks. Helene was almost amazed at how few questions the auction house asked when appraising the fake Valmier: “Normally, a person would think that these experts would study the painting and look for proof of its provenance. [The authenticator] asked two or three questions. She was gone in 10 minutes,” she insisted.

The pirates of the art market

The Beltracchis were astute enough to know that it wouldn’t always be that easy. Three years after they sold the sham Valmier, they crafted a backstory which they would rely on for years to explain the spotty provenance of the vast quantity of forgeries they intended to pass off on unsuspecting auction houses and collectors.

Helene claimed to have inherited an incredible collection from her maternal grandfather, Werner Jägers, a wealthy industrialist who had recently passed away. She would explain to gallery owners and collectors that Jägers had been friends with German-Jewish art dealer Alfred Flechtheim. In 1933, months after Adolf Hitler came to power, Flechtheim fled into exile in Paris, and the Nazis seized his galleries in Düsseldorf and Berlin. But just before this, according to Helene, Flechtheim sold a cache works at bargain-basement prices to Jägers, who hid them in his country home in the Eifel mountains, near Cologne, safe from Nazi plundering.

Though Jägers was legitimately Helene’s grandfather, there were some notable holes in the story. For one thing, Jägers had been a member of the Nazi Party in the 1930s, casting doubt on whether he would have befriended a Jewish dealer. For another, the age discrepancy between Jägers and Flechtheim would’ve made their friendship highly unlikely. The story held just enough water, though, that it helped the Beltracchis skate just under the radar for years.

The Beltracchis were determined to bolster their hoax by any means necessary. Not only did they take a staged snapshot of Helene pretending to be her own grandmother and carefully print it on pre-war paper, but Wolfgang Beltracchi began pasting phony labels onto the backs of each artwork’s frame, something he hadn’t tried with his previous fakes.

The labels, which Wolfgang stained with tea and coffee to create a patina of age, displayed a caricature of Alfred Flechtheim, the Jewish collector who had supposedly provided Jägers with so many paintings, and proclaimed that the paintings were from the “Sammlung Flechtheim”—the Flechtheim Collection. The tags may have lent credibility to the false narrative the Beltracchis had concocted, but it would also be one of the factors leading to the couple’s eventual downfall. Wolfgang and Helene wouldn’t realise it for years yet, but they had made their first mistake.

The narrow escape

By 1995, Beltracchi had made another mistake—one which meant he was on the verge of getting caught for the first time. He had used a pigment that had not been invented until 1957 to paint a Molzahn forgery supposedly painted in the early 1920s. A scientific investigation had found that that painting, as well as two more purported Molzahns, were counterfeit—and police suspected that Beltracchi had been involved in selling those fraudulent works.

Somehow, the Beltracchis escaped the dragnet seemingly closing in around them. The couple has always insisted that they didn’t run away—but it’s difficult to draw a different conclusion from their furtive reaction. The couple abruptly sold their house in Viersen for $1.7 million, told a scant few people where they were headed, and packed into a camping car for Spain.

They eventually settled in a luxury estate, Domaine des Rivettes, in Languedoc-Roussillon. In between dabbling on the stock exchange and driving his Jaguar over to Andorra for the weekend, Wolfgang oversaw the estate’s costly renovation—the Beltracchis added a sumptuous garden and a mausoleum where the forger hoped to be buried one day— and worked in secret on his greatest “masterpieces” in an upstairs atelier.

Beltracchi’s business was booming. By the turn of the millennium, he was making in the high six digits for each of his fakes. His whole story might be Hollywood-worthy, but he had a particular brush with the silver screen when he sold a counterfeit Campendonk to actor Steve Martin. Martin, a long-time art connoisseur, only realised he had owned a fake years after he sold the forgery at Christie’s. The Father of the Bride actor later remarked that the Beltracchis “were quite clever in that they gave it a long provenance and they faked labels, and it came out of a collection that mingled legitimate pictures with faked pictures.”

Beltracchi was doing so well, in fact, that he began to get cocky. Imitating the works of second-tier expressionists and cubists was fairly safe, and the forger had further insulated himself by letting Helene do all the talking to clients. But Beltracchi gradually moved into forging the works of more well-known artists such as Fernand Léger and Max Ernst—paintings that he could sell for higher prices, but that also ran the risk of inviting closer scrutiny.

The experts

For a long time, the Beltracchis managed to weather this increased attention by sticking to a routine carefully designed to cover their tracks. For one thing, Wolfgang himself never interacted with clients. He left that to Helene, or to their front man Otto Schutte-Kellinghaus. Schutte-Kellinghaus, whose pale skin and habit of dressing all in black reminded Beltracchi so much of a vampire that he nicknamed him “Count Otto”, was useful for pulling the wool over art dealers’ eyes. Convinced that “Count Otto” knew nothing about the art world, they never suspected that he might be part of a conspiracy to trick them into paying millions for forgeries.

The Beltracchis’ modus operandi also depended on ensuring that clients never asked for a scientific analysis proving the provenance of the works they had bought. For this, the enterprising couple relied on securing authentication from the most renowned art specialists, who flocked to acclaim the prolific forger’s output as genuine Braques or Légers.

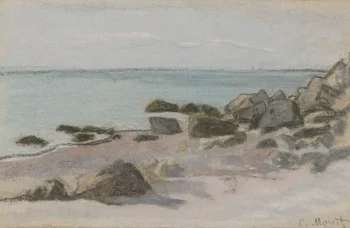

Beltracchi’s expertise proved enough to trick even Werner Spies, a 67-year-old renowned Ernst expert and former director of the modern-art museum at the Pompidou Center in Paris. He went to Beltracchi’s house to see “The Forest (2)” and immediately declared it authentic. Spies quickly put Helene in touch with a Swiss art dealer—Yves Bouvier, a major source of controversy in the art market in his own right—who triumphantly sold Max Ernst’s long-lost The Forest (2) to a company called Salomon Trading, for about €1.8 million, or $2.3 million.

The painting passed to a Paris gallery, Cazeau-Béraudière, which flipped it in 2006 to publishing tycoon Daniel Filipacchi for $7 million. “With Beltracchi, I was one of the losers,” Bouvier said. “Even though I bought works with their certificate from established dealers.” Tricking someone like Yves Bouvier is no easy feat—but Helene claims even Ernst’s widow called “The Forest (2)” “the most beautiful picture Max Ernst had ever painted.”

The downfall

Beltracchi may have managed to hoodwink art experts like Werner Spies and Yves Bouvier. But the good days—during which the Beltracchis jetsetted around the world, sent their children to the finest schools, and bought lavish homes where they installed €700,000 swimming pools—couldn’t last.

The master forger had already made two mistakes. He had pasted the phony Flechtheim Collection labels on the paintings he had created for his wife’s “collection”. He had been sloppy with one of the Molzahns, using an anachronistic pigment. And now he made a third mistake, which would prove fatal to his carefully-constructed operation.

In late 2006, Helene’s sister brought a fake Campendonk to Lempertz. The famed auction house resold it to a Malta-based company, Trasteco Ltd., for €2.8 million. Unexpectedly, the buyer demanded that Lempertz provide an authenticity certificate—which obviously had never existed. Unsatisfied with the auction house’s response, Trasteco hired Andrea Firmenich, a Campendonk expert who had previously assembled the comprehensive catalogue of his works and had authenticated a number of works created by Beltracchi.

Firmenich, who would later deem the damage wrought by the Beltracchi’s schemes so devastating to her reputation that she was reluctant to comment on news pieces covering the scandal, submitted the work for chemical analysis in Munich.

The analysis, which the Beltracchis had long staved off thanks to their careful courting of experts, was damning. It showed that the work contained a pigment, titanium white, that did not exist in 1914. Beltracchi normally sent samples of each paint he used to labs, to ensure that all pigments were available at the time the artist he was copying lived. But this time, convinced that no one would ever catch on to his game, he had slipped up, using a tube of “Zinc White” which contained 2% of titanium white.

For the Beltracchis, the lawsuit marked the beginning of the end of their cushy situation, though they remained free from prison for a few years yet. The German police, working in coordination with the preeminent art experts, began finding more and more paintings with phony “Flechtheim” labels. They eventually contacted Werner Jägers’s family members and learned that his art trove, supposedly the source of Wolfgang and Helene’s “long-lost masterpieces”, was a sham. The game was finally up for the dynamic duo, who had made an estimated $22 million in profit from their fraudulent scheme.

The consequences

Early in the morning on August 27, 2010, five police vans surrounded the Beltracchis’ car as they were leaving their luxury home in Freiburg. “It was like Miami Vice”, Wolfgang recalled later about the dramatic raid. Their trial, which Der Spiegel correspondent Michael Sontheimer deemed “a farce”, began a year later in Cologne.

From the start, the Beltracchis charmed the media and courted public opinion, portraying themselves as innocent pranksters who had only preyed on the rich. In his long confession Beltracchi played to the gallery, describing his wild countercultural youth and attacking the “greed” and “arrogance” of the overheated art market. “[The art experts’] only problem was that I was too good for them”, Beltracchi declared confidently. “Whoever criticizes me just wants revenge—or they are jealous.”

To make matters worse, the prosecution struggled to present decisive evidence that Beltracchi had created the fakes, and in October 2011 the judge overseeing the case announced that the two sides had reached a deal. Wolfgang and Helene plead guilty to having forged a mere 14 paintings, and in return received relatively light sentences: incarceration for just six and four years, respectively, with time off for good behaviour. What’s more, the pair were allowed to serve out their sentences in so-called “open prison”, which they were allowed to leave during the day to work together in a photo studio.

“It doesn’t look like much of a punishment”, the New York Times concluded, and René Allonge, the Berlin policeman who had overseen the investigation into the Beltracchis, was inclined to agree. “A German court judged these people, and I’m not at liberty to comment,” he remarked after boycotting the sentencing. “All I can say is that I don’t find it good when someone walks out of the courtroom so sure of victory. There are similar criminals who faced much more severe punishment, who have to spend a lot longer time in jail. I don’t think this leaves a good impression.”

The Beltracchis’ legacy

Indeed, the Beltracchis seem to have had the last laugh in the end. Since Wolfgang was released in 2015, the pair have milked the notoriety their criminal past brought them for all it’s worth. They have published several books—including a collection of love letters which Wolfgang and Helene wrote each other while they were imprisoned—and come out with a documentary. The master forger is still selling paintings for handsome fees—this time under his own name. He even has a plan to start a Swiss television show called “Academia Beltracchi”, in which he will travel around with art students and teach them art history.

The art world, meanwhile, is still struggling to cope with the ramifications of the most lucrative art forgery ring in history. Beltracchi remains an incredibly polarising figure. Art market expert Ralph Jentsch, who help uncover his forgeries, says Beltracchi’s work was “rubbish” and “crude fakes” that only the sloppiness and laziness of some art market experts made seem legit. Daniel Filipacchi still loves “The Forest (2)” but insists that Beltracchi signs it with his name. The forger’s gallerist, Curtis Briggs, has referred to him as “the Robin Hood of art”—despite the fact that nobody profited from his fraud more than Beltracchi himself.

Sure, he helped expose the greed and negligence of art market players, who only pay money for names, not for the art itself. But his forgery scheme had nothing to do with getting the market straight or helping the poor, he only helped himself and his family—with huge collateral damage along the way. Spies, who certified seven of Beltracchi’s fake Max Ernsts, admitted to a German magazine that he had briefly considered killing himself after the scandal broke. “How could I bear the knowledge that I was taken in?” he explained. “The loss of my reputation! It made me think that I should say good-bye to this world.”

However, the Beltracchis’ biggest legacy, though, may be reflected in the spate of recent headlines showing that there are plenty of forgers following in their footsteps.