Walking into the first gallery space of Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset’s ‘This Is How We Bite Our Tongue’ at the Whitechapel Gallery feels confusing yet enticing. The duo is known for their sculptures, architectural installations, and public commissions and this exhibition does not shy away from the uncanny spaces and rich narrative they trend towards. ‘This Is How We Bite Our Tongue’, Elmgreen and Dragset’s first UK survey exhibition, ties together themes they have experienced throughout their career of how spatial context affects our behaviors, sexual identity, and social responsibility.

The gallery’s lack of wall text means you are not blatantly directed to any part of the exhibition. Instead, you navigate the space more organically and at times hesitantly. I found myself asking gallery attendants if I was walking through the correct doors as I passed through what became three distinct sections: the Whitechapel Pool, Self-Portraits, and the final gallery.

Crossing the threshold from ticket desk into the public swimming pool-cum-gallery space you second guess if you are in the correct area – particularly if you’re lucky enough to walk in at a point when no one else is in the room with you. The sterile, hospital-like green that adorns the lower half of the walls feels medical in the fluorescent lighting. A number of sculptures litter the pool deck promoting the overarching feel of break down. The setting itself is a bygone period of civic centre; that which once thrived has fallen into dismay. Changing Room/Powerless Structures, Fig. 128 consists of a door that seems normal but upon closer inspection the viewer realizes it has hinges on both sides making it impossible to use. Labelled ‘Changing Room’, the door does not allow for change or function representing the breakdown in structure.

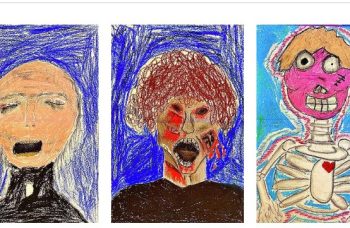

Moving upstairs, visitors enter the Self-Portrait gallery where one expects figural images, but instead is greeted by the familiar sight of exhibition wall labels, albeit very oversized. These labels bear the names of other artists and their works through traditional mediums including carved white marble and oil on canvas. The labels represent the artists and works of art that have influenced and inspired Elmgreen and Dragset throughout their work.

The Self-Portrait gallery transitions the viewer from the sterile feel of the pool room to the dark feel of the final gallery. This space contains seven sculptures tied together by colour palette and choice of material. The sculptures, though, diverge from here crossing notions of masculinity, childhood, self-identity and identity, and religion to name only a few themes. Material ties sculptures in this space to those in the pool room. The duo utilizes bronze for a number of objects in both galleries but Elmgreen and Dragset manipulate the material in a manner that deceives the eye.

The spaces in-between the galleries become interesting transitions and hold works like Modern Moses, an ATM with an abandoned child below it, and Powerless Structures, Fig. 19, two pairs of blue jeans abandoned in the rush of undressing. These works are only two of the many works in the exhibition that leave the viewer to fill in the gaps of what has happened. These liminal spaces link the more concrete themes of each room. Much like their well-known Prada Marfa (2005) or Van Gogh’s Ear (2016) it becomes obvious that Elmgreen and Dragset do not want to give the full story leaving viewers to consider why we bite our tongues.