You hear Mikhail Karikis’s No Ordinary Protest, before you see anything as you move from gallery to gallery in the Whitechapel Gallery. The dark blue walls are interrupted by the glow of UV masks in the images and video that runs while the expected silence of the gallery is disturbed by a mix of children’s voices and eerie noises that seem to be nonsense. The combination is nothing less than startling.

Karikis teamed up with the Mayflower Primary School in East London and drew inspiration from British writer, Ted Hughes’s 1993 children’s science fiction novel, ‘The Iron Woman’ to create the uncanny experience. The ‘ecofeminist’ narrative, for those unfamiliar, tells the story of a female superhero who gives children the atypical power, transmitted through touch, to hear the sounds of the ‘creatures’ poisoned by adults. Children thus become the antidote to the toxic ways of adults.

Commissioned by Film and Video Umbrella, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, and Whitechapel Gallery, Karikis’s installation crosses the boundaries of film, performance, and sound. The final product is eerie, beautiful, imaginative, strange, child-like, yet elegant.

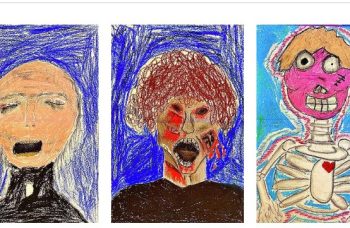

Welcoming viewers is a larger still from the video at eye level of what you eventually realize are children wearing handmade masks painted in UV paint. The image glows at the onlooker. In the same space, a second large image of five children cross-armed wearing larger, more elaborate headpieces only adds to the creepy fun-house quality of the subject matter.

Perhaps most unsettling, though, is the mix of indistinguishable noises that spearheads the installation and radiate through the gallery. Slow motion video of mask-clad children glows before the viewer while the strange noises intensify. Then, just as strangely as it all comes on, the noise halts.

After the strange sight of the UV masks and odd noises, the film shows children discussing and explaining Hughes’s story. Mulling over notions of human versus animal, it is intriguing to watch children, who in the novel would be the answer to the world’s problems, discuss the problems that come from the ‘poison’ administered by adults.

Suddenly, what seemed nonsensical becomes clearer. Karikis’s installation highlights, with UV paint, the environmental themes that are not distant from our world and themes of how these issues have arisen and who might be able to fix them. No Ordinary Protest forces viewers to consider how the issues tackled by children in a fictional novel are really the issues of modern society.

One pitfall that undermines the installation is the stream of museum guests filtering from the lift to other galleries. However, upon closer inspection, perhaps, the stream of guests that walk between those watching the video and the screen itself may play a significant role in the installation. Are they like the adults in the story? Are they the ones that ignore environmental issues and that ignorance acts as the ‘poison’ that suffocates the environment? This might not have been Karikis’s vision but No Ordinary Protest is also no ordinary installation running through 6 January 2019.