The Italian artist Francesco Clemente has been a fixture of the art world since the 1980’s. An extensive exhibition of his work at the Brant Foundation in Greenwich, CT, begins with an emphasis on his prominence in the New York City scene.

The Italian artist Francesco Clemente has been a fixture of the art world since the 1980’s. An extensive exhibition of his work at the Brant Foundation in Greenwich, CT, begins with an emphasis on his prominence in the New York City scene.

First Impressions

Humble watercolor portraying portraits Keith Haring and Jean Michel Basquiat refer to Clemente ‘s early days, as a young artist who loves the likes of Andy Warhol. And more consistently, Clemente’s work has been exhibited in America and Europe.

Stylistically, Clemente has been remarkably consistent, confidently pursuing his ideas as trends and goings. This latest comprehensive overview is a testament to his commitment and consistent production.

Ashram Artist

Clemente, who grew up in Italy, is a longtime New Yorker. The artist is known for his “nomadic” style, as well as the philosophies of the East – particularly of India where he traveled as a young man – have significantly influenced his work.

In the Brant exhibit, just beyond the opening room of portraits, hang dozens of small watercolor and pastel works on paper, which were completed by Clemente in a diaristic fashion while staying at an ashram between 1979 and 1980. Many of the humble sketches, which linger across delicate, tanned paper, portray himself in a thin, wavy lines, interacting with one of his “orifices” (plugging his nose, covering the ears or eyes).

These unusual representations convey the experience of a meditator who has become aware of the physical senses and interfaces with the outer world – in contrast to the deep stillness and subtlety of the inner world. Many of the other snapshots in this series portray everyday objects – unselfconsciously, sometimes crudely, yet delicately – such as fruit, flowers, shoes, imbuing them with the enigmatic magic of an alchemical diagram.

Installation of Clemente paintings at the Brant Foundation. Photograph by Laura Wilson, courtesy of the Brant Foundation.

Neo-Expressionist Canvas

A series of large-format oil paintings follow. The Neo-Expressionist works, executed between 1978 and 2018, all find their cozy, temporary home in the Brant’s gallery, featuring exposed wood trusses and ridged skylight that allow for abundant natural light.

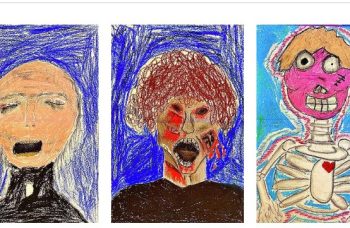

A darker, more caustic dimension to Clemente’s exploration is evident in several of these works. This spiritual portrait is particularly evident in a canvas, titled “Name” (1983), which pictures an extremely pale self-portrait. The orifices of this face – ears, nostrils, eyes and mouth – are all chillingly replaced with replica faces.

This review is a reflection of Guggenheim retrospective in 1999, noted the dual influence of Eastern and Western – mystical and existential – angst. And yet conceptually interesting, for me, the composition resembles a movie poster that a high-school movie buff might envision; it’s clear in a proposed terrorizing surreality, but somehow easy.

For me, this was the first inkling, that Clemente’s naive style may have read in 2019, than it was a few years ago – a time when figurative painting was considered dead, and Clemente, among others, made it to revive it.

Some works triumph still, and this included an ever-fresh canvas of pale pink and cherry red, titled “Scissors and Butterflies” (1999). The romantic, sensual darkness found in the Hindu and Yogic traditions, which revere a goddess named Kali, is traceable in this canvas; demonic ladies, seemingly dangerous as they are intriguing, precariously handle scissors, pointing them at one another’s orifices.

Installation of Clemente works at the Brant Foundation. Photograph by Laura Wilson, courtesy of the Brant Foundation.

Tantric Fresco Temple and Immersive Tent

Francesco Clemente’s lyrical expressions of mystical love, a tale inspired by the Tantric tradition of the East, which is one of a kind of conflict between body and spirit, and which uses sexuality and metaphor for transcendental experiences, a two-storied room in the back of the Brant Foundation’s galleries.

Six towering frescoes, the mystical symbolism of which emphasizes circles and areas of color, are reminiscent of Hilma af Klint. In the center of the room, immersed in a full-size, viewers are surrounded by Clemente’s encyclopedic mastery of iconography, as a myriad of disparate figures, patterns and potent symbols decorate the fabric.

Watercolor Symbolism

A colossal series of allegorical watercolor paintings line the parameter of a sprawling basement gallery. The callow drafting style of these massive watercolors, in which cartoonish hearts lay inside brick structures, and figures first struggle and eventually rejoice, across a washy rainbow background, is overcome by the sheer impact of such a monumental display.

An intimate series of small watercolors represents a feminine entity — possibly the goddess Shakti of Eastern mysticism — in various guises. In the Tantric traditions that Clemente is influenced by, the feminine goddess represents nature, the instinctual energy that activates and inspires life (both cosmic and personal). These improvisational watercolors truly convey the feeling of meditative ecstasy. With exacting lines and lush color, Clemente portrays the essence of eternal life force as a woman with round hips, abstracted breasts and swirling, rune-like yonis (genital areas).

To Close the Show

The fresh, unrestrained life — the sparks of mystic insight — emanating from the previous works were undermined by what felt like an addendum, a room of afterthoughts, which was effectively a punctuation to the Brant’s tour. Unfortunately, a series of modest paintings, centering upon Sanskrit script, read like New Age kitsch that one might pick up further upstate. Nonetheless, there is the feeling that Clemente doesn’t mind any such association, as he explores his themes naturally, unaffected.

The disparate range of Clemente’s work is revealing of a creative practice that is driven by a highly individual and eclectic spiritual, philosophical and aesthetic ideology. Clemente is the real-deal, whether or not all of his many works from across the decades seem to fancy the eye of every overly-keen onlooker.